Grasping for inspiration has plagued many artists, and for a long while, humanity thought that there was a goddess out there in the firmament that could provide a nudge in the right direction, encouraging the artist to put pen to paper or brush to canvas. There was this little notion of a muse. And I suppose it was a comforting conceit for eons. Look at the John Keats poem “Ode to Psyche.” It starts: “Oh Goddess hear thy tuneless numbers wrung from sweet enforcement and remembrance dear, and pardon that thy secrets should be sung, if even into thine own soft-conchéd ear.” This poem is a love letter to an abstraction – albeit a comforting one. We have lost touch with this possibility, that something outside of us can somehow help us to engage with our creative pursuit. We have become all too self-reliant, and possibly much to our detriment. Maybe ardent supplication to the goddess is necessary once again. By invoking this fantastical creature, Keats is striving to transform the ideal he sees in his head, the perfect poem, into something very mundane – the steady movement of his fingers, holding a quill, over the parchment. He isn’t expecting much – most efforts just produce the “tuneless numbers” to which he refers. But there is value in the workman-like iterations. Every once in a while, one of those numbers transcends even the ideal that was once in the artist’s head. The artist sees through the muck and produces something that has special appeal and enduring value. The work says something more than the sum of pencil strokes upon the paper. This must be the strange adventure of creativity – to be forever chasing after a muse, or a voice, or whatever you might call it. But there must be a more efficient way to pursue this quarry, to get at such close quarters that you can whisper its secrets into its ear.

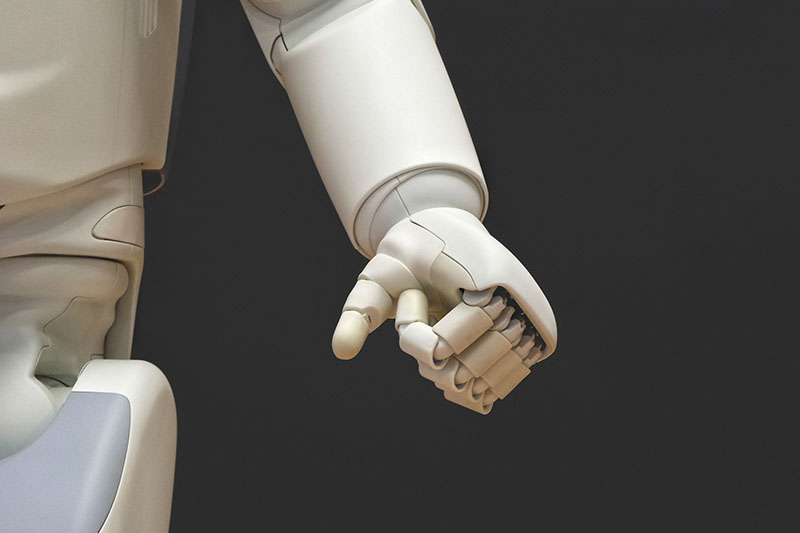

Photo by Possessed Photography on Unsplash